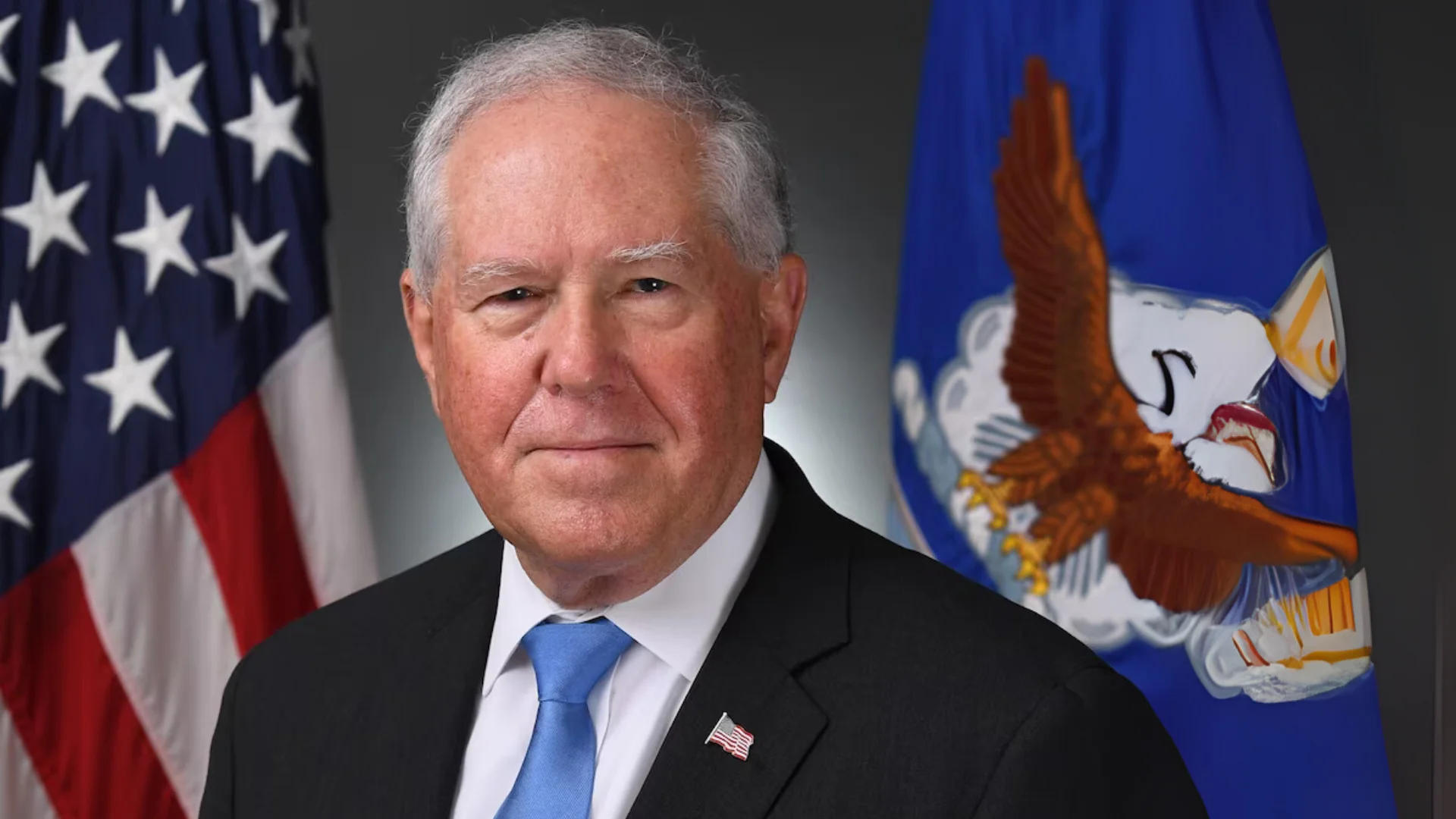

Former Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall responded to these remarks by telling Breaking Defense: "It’s an option that was never presented and that we never considered, to my knowledge." Reconfiguring the F-35 with more than one engine would require a significant redesign of the aircraft.

The Pratt & Whitney F135 engine powers all versions of the F-35: A (conventional takeoff), B (short takeoff/vertical landing), and C (carrier-based). The STOVL capability of the B variant is enabled by Rolls-Royce's LiftSystem. The F135 was chosen over competing designs from General Electric/Rolls-Royce following a competitive process.

First delivered in 2009 and derived from the Pratt & Whitney F119 used on the twin-engined F-22 Raptor, over 1,300 production units of the F135 have been delivered. The engine delivers up to 43,000 pounds-force (lbf) with afterburner (41,000 lbf for STOVL variants) and about 28,000 lbf without afterburner.

Stealth characteristics are central to its design; advanced thermal management helps reduce detectability compared with other high-performance engines such as Russia’s Saturn AL-41F1 used on non-stealthy Su-series aircraft.

Continuous upgrades aim to reduce fuel consumption and maintenance needs while increasing reliability—key factors for extending range given tanker aircraft vulnerabilities. Future improvements will come through an Engine Core Upgrade as part of Block IV enhancements planned around 2029.

Pratt & Whitney claims high reliability rates for its engine: "delivers a generational leap in performance and reliability" and “continuously exceeds full mission capability rate requirements of 94%.” The company also states that its safety rate is “more than an order of magnitude better than previous generations of fighter engines” across life cycles.

Maintenance processes are streamlined by design; all line-replaceable components can be serviced using six common hand tools. A digital health management system allows maintainers real-time status updates and troubleshooting before aircraft return from missions.

The STOVL-capable F-35B uses a modified version—the F135-PW-600—which includes heavier construction (7,260 lbs dry weight) but enables vertical landing through integration with Rolls-Royce’s lift fan system. About half of downward thrust comes from this lift fan; another nearly half from a vectoring exhaust nozzle; small nozzles in each wing provide additional control.

Countries planning or already ordering substantial numbers of these jets include Australia (100), Japan (147), Italy (115), Israel (75), Canada (88), Germany (35), South Korea (60), Switzerland (36), Denmark (27), Finland (64), Norway (52), Poland (32), Belgium (45), Czech Republic (24), Greece (20), Netherlands (57), United Kingdom (138) and United States with over two thousand orders placed or intended.

The decision by Lockheed Martin to use this advanced propulsion system contributed significantly to winning contracts against competitors like Boeing's X-32 during development trials.

While not designed for extreme speed—maximum cruise Mach was reduced from plans for Mach 1.8 down to Mach 1.6—the focus remains on stealth rather than velocity. Modern combat experience suggests high speeds compromise stealth capabilities due to increased heat signatures while offering limited tactical advantages under most operational scenarios.

Looking ahead at sixth-generation fighters—including projects such as Anglo-Japanese Tempest/GCAP—designers appear set on returning to multiple-engine configurations due partly to increased size requirements and greater power demands for new onboard systems such as sensors or directed-energy weapons.

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up